Lesson 1: Using Openly Licensed Works Published by Others#

Vignette: A Cautionary Tale of Unlicensed Code

Dr. Emily Johnson, a postdoctoral researcher in computational physics, has been working on a complex simulation software for modeling quantum systems. After months of hard work, she finally has a working prototype that she believes could be useful to other researchers in her field. Excited to share her creation, Dr. Johnson uploads the source code to a popular code repository, along with a brief README file describing its functionality. She eagerly awaits feedback from her colleagues, hoping that her software will contribute to new discoveries in quantum physics. A few weeks later, Dr. Johnson gets an email from Dr. Robert Nguyen, who stumbled upon her code repository. He expresses his interest in using the software for his own research project but is hesitant to do so without knowing the terms under which he can use, modify, and share the code. He asks Dr. Johnson if she could clarify the licensing terms for her software.

Surprised by the request, Dr. Johnson realizes that she had not explicitly specified any license for her code. She had assumed that by making the source code publicly available, she was granting permission for anyone to use it freely. She now understands that simply making the code public does not make her project open source. In fact, without a clear license, her software is essentially in a state of legal uncertainty. Potential users, like Dr. Nguyen, are left wondering if they have the right to use, modify, or distribute the code. Many well-informed researchers may choose to avoid using her software altogether, as the absence of a license makes it unclear whether they can do so without legal risk. Dr. Johnson realizes that by not attaching a license to her software, she unintentionally limited its potential impact and adoption within the scientific community. She learns that software, like poetry or any other creative work, is automatically protected by copyright law the moment it is created. Without a clear license, users are forced to assume that they do not have permission to use or build upon the work.

To rectify the situation, Dr. Johnson decides to research software licenses and choose one that aligns with her goals of fostering collaboration and open science. By attaching a standard open-source license to her software, she can grant users the necessary permissions and freedoms, while still retaining credit for her work. This experience teaches her the importance of specifying a license for her software projects from the outset, ensuring that her work can be used, shared, and built upon by others in the scientific community.

Open licensing concepts#

In the world of research and education, open licensing has become increasingly important for enabling the free exchange of ideas, promoting collaboration, and accelerating scientific progress. But what do we mean by “open licensing”?

In essence, open licensing refers to a set of principles and legal frameworks that grant permissions for others to freely access, use, modify, and share creative works or products. This concept applies to various types of outputs, including software, research data, scholarly publications, and educational materials.

Open-source software is perhaps the most well-known example of open licensing. Open-source licenses, such as the MIT, BSD, and Apache licenses, allow users to access the source code of a software program, study how it works, modify it to suit their needs, and redistribute the modified versions.

Similarly, the open data movement advocates for making research data openly available and reusable, often under licenses like the Open Data Commons licenses or Creative Commons Zero public domain dedication. This enables other researchers to validate findings, combine datasets, and build upon existing work.

Open content licenses, like the Creative Commons suite of licenses, are commonly used for scholarly publications, educational resources, media files, and other creative works. These licenses grant varying levels of permissions for reusing, redistributing, and modifying the licensed content.

The principles of open licensing are deeply rooted in the academic traditions of sharing knowledge, enabling peer review and scrutiny, and fostering collaborative advancement of human understanding. By embracing open licensing, researchers and educators can:

Increase the transparency and reproducibility of their work, a cornerstone of the scientific method.

Facilitate the dissemination of their findings and educational materials to a wider audience, amplifying their impact.

Build upon the work of others, accelerating the pace of discovery and innovation.

Collaborate more effectively with colleagues across institutions and disciplines, breaking down silos and fostering interdisciplinary research.

Open licensing is not just a technological or legal construct; it represents a cultural shift towards openness, collaboration, and the democratization of knowledge. As we go deeper into this topic, you will learn the practical aspects of using openly licensed works, and what to consider when licensing your own research outputs and collaborating with others in open-source projects.

Important

Open licensing gives us freedom—contrary to intellectual-property instruments that want to control how creative works are used.

Freedom is power. In this case, the power of open-source software comes not just from being able to read the source code, but from being able to contribute to and build from it.

For this power to be realized, it’s not sufficient to make the source public to read. We must attach a license that allows others to modify and distribute the code.

Understanding license types#

Understanding the basic differences between license types is essential for researchers and educators who want to make informed decisions about which licenses to use for their own projects and how to properly use and attribute third-party software in their work. By familiarizing yourself with the key characteristics and implications of each license type, you can ensure that you are using and sharing software in a way that aligns with your goals and values, while also respecting the rights and intentions of the original creators.

The three main categories of licenses are: open-source permissive, open-source copyleft, and proprietary.

- Open-source permissive licenses

Open-source permissive licenses, such as the MIT, BSD, and Apache licenses, are designed to grant users broad freedoms to use, modify, and distribute the licensed software. These licenses typically only require that the original copyright notice and license text be included in any copies or derivative works. Permissive licenses place minimal restrictions on how the software can be used, making them popular choices for academic and research projects. They allow for easy integration with other software projects, including proprietary ones, making them ideal for promoting widespread adoption and collaboration.

- Open-source copyleft licenses

Open-source copyleft licenses, like the GNU General Public License (GPL), GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL), and Mozilla Public License (MPL), are designed to make sure that the freedoms granted by the license are preserved in any derivative works. Copyleft licenses require that any modifications or additions to the licensed software also be released under the same license terms. This “share-alike” requirement ensures that the software and its derivatives remain open and accessible to all. Copyleft licenses are often chosen by developers who want their work to remain open and freely available in perpetuity.

- Proprietary licenses

Proprietary licenses are the most restrictive type of license. They typically grant users the right to use the software only for its intended purpose, often limiting the ability to copy, modify, or redistribute the software. Proprietary licenses are commonly used for commercial software products, where the source code is kept closed and the software is distributed only in binary form. Examples of proprietary licenses include the End-User License Agreements (EULAs) that accompany most commercial software packages.

Composing works under different licenses#

As a researcher or educator you’ll likely find yourself wanting to use code, data, or content from multiple sources in your projects. But before you start mixing and matching, it’s crucial to understand how different licenses can work together (or not!) and the implications of combining them.

What is license compatibility?#

Some licenses play nicely with others, while others have strict requirements that can limit their compatibility. When combining pieces of code together, you will want to check whether the terms of their different licenses allow them to be used together in the same project.

For example, let’s say you want to use a Python library licensed under the permissive MIT license in your research project. You also want to include a dataset licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. In this case, you’re in luck! The MIT and CC BY licenses are generally compatible, meaning you can use them together without any legal hiccups.

License directionality#

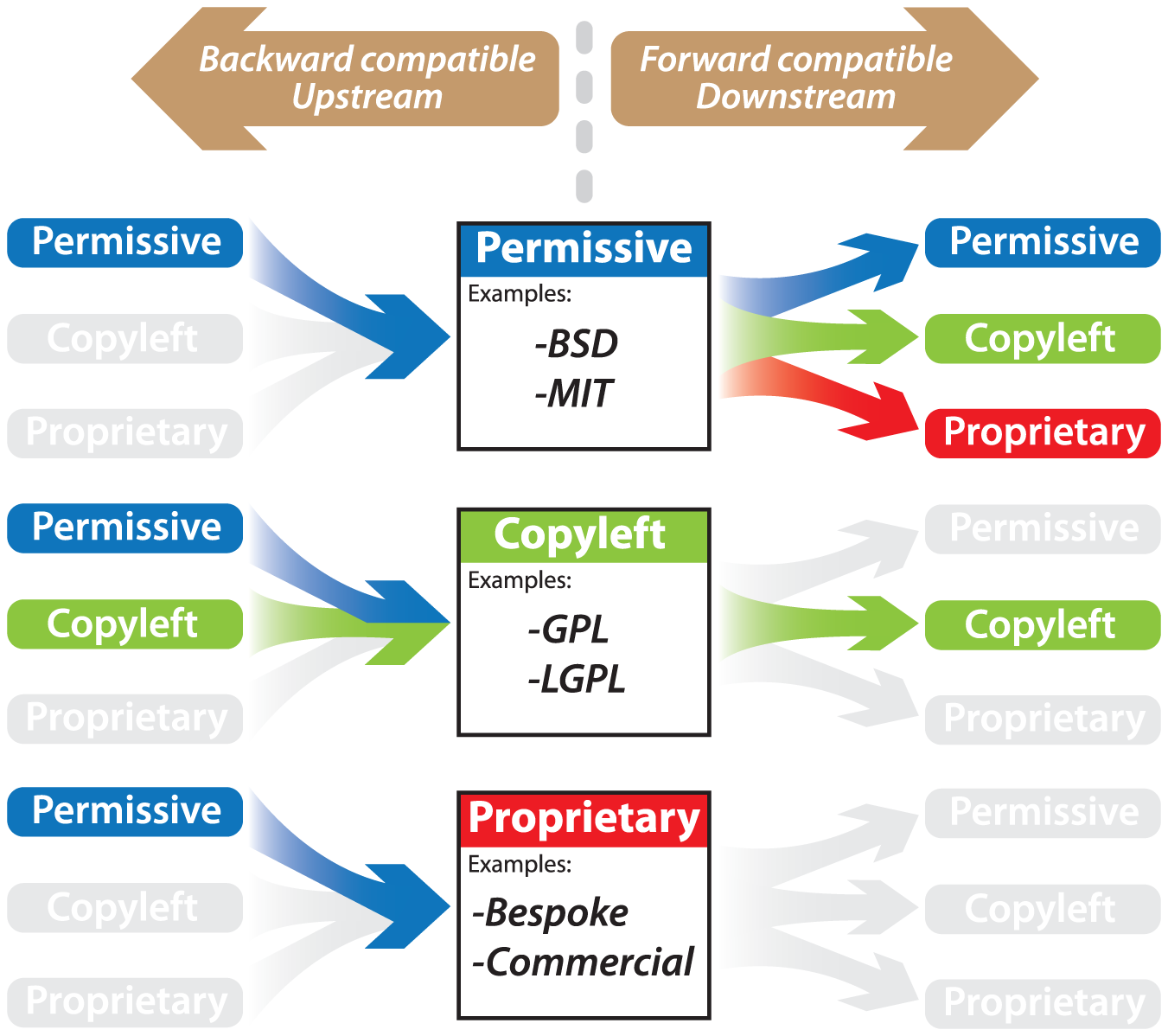

Now, let’s talk about license directionality. This concept refers to how a license behaves differently depending on whether it’s applied to code, data, or content that is being incorporated into your project (upstream) or to the resulting work you create (downstream).

Imagine you’re building a research software tool that analyzes social media data. You plan to use a sentiment analysis library licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL), which is a copyleft license. If you incorporate this GPL-licensed code into your project, the terms of the GPL require that your entire project also be licensed under the GPL when you distribute it. In this case, the GPL license is said to be “viral” in the downstream direction, affecting the licensing of your derived work.

Similarly, if you’re using a dataset licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) license, you’re required to distribute any derivative works under the same license terms. However, this requirement only applies to the dataset and any modifications you make to it, not to your entire project. The CC BY-SA license is considered “viral” only for the dataset, not for the larger work it’s incorporated into.

Fig. 1 License directionality. Schematic under CC-BY from Morin et al. [MUS12]. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002598.g002#

Combining code, data, and content under different licenses#

Now, let’s put it all together. When you’re combining code, data, and content from different sources in your research or educational projects, it’s essential to consider the compatibility and directionality of their respective licenses.

Say you’re creating an online course that includes a mix of your own content, images licensed under Creative Commons, and code examples from various open-source projects. You’ll need to review the licenses of each component to ensure that they are compatible with each other and with the license you choose for your overall course materials. A handy tool to help you with this task is the Creative Commons License Compatibility Chart.

Understanding license compatibility and directionality is key to making informed decisions when using and combining licensed works in your research and educational projects. Take the time to review the licenses of the components you use, and always confirm that you are using them legally and ethically.

Important

If you find code or other content on a public repository or website, and there’s no license information, you must assume it is “all rights reserved.” If it looks like the author meant for their work to be reused, you can contact them (or open an issue in the repository) asking them to add a public license.

Examples of OSS for researchers and their license terms#

Python, NumPy, R, BioPython, LAMMPS, NWChem, Quantum ESPRESSO, QGIS…

- Python

Python is a popular open-source programming language widely used in scientific computing, data analysis, and machine learning. It is released under the Python Software Foundation License, a permissive software license approved by the OSI. Thus, all of the Python source code can be reused and redistributed for any use, including commercial. The only condition is that the PSF’s License Agreement and PSF’s notice of copyright be retained in any derivative works.

- NumPy

NumPy is a fundamental package for scientific computing in Python, providing support for multi-dimensional arrays and matrices, along with a collection of mathematical functions. It is under the BSD 3-Clause License, which is a permissive license that allows users to freely use, modify, and distribute the software, with minimal requirements for attribution and no restrictions on commercial use.

- R

R is a programming language and environment for statistical computing and graphics. It is licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL) version 2 or later. The GPL is a copyleft license, meaning that any derivative works must also be distributed under the same license terms. You can use, modify, and distribute R and its packages, but any modifications you make must also be open-source under the GPL.

- Biopython

Biopython is a set of tools for computational biology and bioinformatics written in Python. It is released under the Biopython License Agreement, but many files are dual-licensed under the BSD 3-Clause License. These are both permissive licenses allowing all uses and redistribution, provided that the copyright notice is retained. The Biopython License, however, is not OSI-approved.

- LAMMPS

The Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator, LAMMPS is a software package for high-performance (classical) molecular dynamics simulations for materials science applications.It is distributed under the terms of the GNU Public License Version 2 (GPLv2), so any software that uses or includes LAMMPS source code must also be under GPL.

- NWChem

NWChem is a computational chemistry software package for both quantum chemical and molecular dynamics simulations, distributed under the terms of the OSI-approved Educational Community License, ECL 2.0. The ECL is a permissive license that allows free use, modification, and distribution of NWChem, including for commercial purposes, as long as the copyright notice and disclaimer are retained.

- Quantum ESPRESSO

Quantum ESPRESSO is a software suite for electronic-structure calculations and materials modeling at the nanoscale, with contributions from many research groups around the world. It is distributed under the GNU General Public License (GPL), a copyleft license requiring any modifications or derivative works to also be open-source under the GPL.

- QGIS

QGIS is a popular open-source geographic information system (GIS) used for mapping and spatial data analysis. It is licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL) version 2 or later. Like with R, above, any modifications or derivative works of QGIS must also be distributed as open-source under the GPL.

Giving credit where credit is due: citing openly licensed works#

As you’ve seen already, openly licensed software, data, and content play a key role in enabling reproducible, collaborative, and innovative research. So it’s not enough to use and build from these resources; we also have an obligation to properly credit and cite them in our work.

Citing openly licensed works is important because:

It gives recognition to the creators who have generously made their work available for others to use and build upon.

It helps others discover and access the resources you’ve used, promoting further collaboration and reuse.

It enhances the transparency and reproducibility of your research by clearly documenting the tools and data you’ve relied on.

In academia, citing software and data is becoming increasingly common and accepted, just as citing research articles and books has long been the norm. Many open-source software projects provide clear guidelines on how to cite them in research publications, often including a suggested citation format or even a DOI (Digital Object Identifier) for stable referencing.

Spotlight on the Journal of Open Source Software (JOSS)

One initiative that is helping to promote the proper citation and recognition of open-source software in research is The Journal of Open Source Software (JOSS). JOSS is a peer-reviewed journal that publishes articles describing open-source software packages, libraries, and tools used in research.

What sets JOSS apart is its focus on the software itself, rather than the research results obtained using the software. Each JOSS article includes a detailed description of the software, its purpose, functionality, and how it can be used by other researchers. Importantly, JOSS articles also provide a standardized way to cite the software, making it easier for others to properly credit and reference the work.

By publishing in JOSS, software developers can receive academic credit for their work, similar to publishing a research article. This helps to incentivize the creation and sharing of high-quality, well-documented open-source software, and promotes a culture of recognition and collaboration within the research community.

Leading by example#

As researchers and educators, we have an opportunity to lead by example in properly crediting and citing the openly licensed works we use. By consistently providing attribution and references for the software, data, and content we rely on, we can help to establish this practice as a community norm and expectation.

Moreover, by introducing our students and colleagues to resources like JOSS and the importance of software citation, we can help to foster a new generation of researchers who understand and value the role of openly licensed works in advancing scientific discovery.

So, as we move forward in exploring the use and creation of openly licensed works, let us remember to give credit where credit is due, and to actively participate in building a culture of recognition and collaboration within the open research community.

Activity: exploring open-source software in your field#

The goal of this activity is to help you gain hands-on experience in identifying, evaluating, and properly crediting open-source software relevant to your research or educational work.

Think of a research topic or educational need in your field that could potentially be addressed using open-source software.

Search for open-source software packages, libraries, or tools that could be used to tackle this problem or meet this need. You can use resources such as GitHub, GitLab, JOSS, or other domain-specific repositories to find relevant software.

Select one or two open-source software packages that seem most promising for your purposes. For each package, do the following: a. Identify the license under which the software is released. Is it a permissive license (e.g., MIT, BSD) or a copyleft license (e.g., GPL)? What are the key terms and conditions of the license? b. Investigate whether the software has been published in JOSS or another peer-reviewed venue. If so, read the associated article to gain a deeper understanding of the software’s purpose, functionality, and potential applications. c. Determine how to properly cite the software in a research publication or educational material. Look for a CITATION file, README, or other documentation that provides guidance on citation format.

Take some notes of your findings for each software package, including: a. The name and purpose of the software b. The license under which it is released and its key terms c. Whether it has been published in JOSS or another peer-reviewed venue d. How to properly cite the software in your work

Share your summary with your colleagues or classmates, and discuss how you might incorporate these openly licensed tools into your research or educational work.

By engaging in this activity, you’ll gain practical experience in navigating the landscape of open-source software, understanding licensing terms, and properly crediting the works you use. These skills will serve you well as you continue to explore the use and creation of openly licensed resources in your work.

Vignette: The Tale of Dr. Flack’s Data Visualization Journey

Dr. Roberta Flack, a climate scientist, needs to create interactive visualizations of global temperature data. After some searching, she finds a JavaScript library called “ClimateViz” that seems perfect for her needs. The library is hosted on GitHub and is released under the MIT license. She also discovers a dataset of global temperature anomalies from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which is available under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license.

Identifying and Complying with License Terms— Before using these third-party resources, Dr. Flack takes the time to read and understand the terms of the MIT and CC-BY licenses. She notes that both licenses allow her to use, modify, and distribute the library and dataset, as long as she includes the original copyright notices and license terms. The MIT license also requires her to include a copy of the license in any distribution of her project that includes the ClimateViz library. Dr. Flack makes a note to include the necessary license files in her project’s documentation.

Attribution and Citation Requirements— Dr. Flack also notices that both the MIT and CC BY licenses require her to give appropriate credit to the original creators of the library and dataset. She reads the library’s documentation and finds that the authors have provided a suggested citation format for academic use. For the NOAA dataset, she finds a similar citation request on the agency’s website. Dr. Flack modifies her project’s README file, ensuring that she gives proper credit to the creators of the resources she’s using. She also includes the citations in her manuscript when she submits her research for publication.

Source Code Availability and Modifiability— As Dr. Flack works with the ClimateViz library, she realizes that she needs to modify some parts of the code to better suit her specific data-visualization needs. Because the library is released under the MIT license and hosted on GitHub, she is able to easily access the source code and make the necessary changes. Dr. Flack also decides to contribute her modifications back to the original project by submitting a pull request on GitHub. She includes a clear description of her changes and the reasoning behind them, hoping that her contributions can benefit other researchers who might be using the library.

By taking the time to understand and comply with the license terms, attribution requirements, and source code availability of the third-party resources she’s using, Dr. Flack ensures that she’s using these open works legally and ethically. Her careful attention to these practical considerations not only helps her advance her own research but also contributes to the broader open science community.

Sources#

Portions of this lesson are based on materials from the presentation by Barba [Bar17], which drew from Morin et al. [MUS12].